- Futás

- Hegymászás

- Kerékpár

- Túra

- Sí

On 26 April 2023, China's Dong Hong Juan climbed to the main summit of Shisha Pangma, 8027 metres above sea level. In doing so, she completed the Crown of the Himalayas challenge, climbing all 14 mountains in the world above 8,000 metres. Paradoxically, she became the first woman to climb all 14 of the eight thousander mountains. A feat that had already been completed more than a decade ago. Who was first then? And what mountaineering value does the 14x8000 have at all today?

First of all, I would like to make it clear that this article looks at these climbing achievements from the perspective of climbing history, not from the perspective of what the average person considers difficult. Climbing 8,000m peaks is inherently difficult, but it only makes sense to compare 8,000m performances by looking at the style they are climbed with. And you don’t have to be an 8000er climber to see the differences.

For four decades, renowned German chronicler Eberhard Jurgalski has been collecting climbing data on the world's eight-thousanders and has been publishing data on 8000ers.com since 2008. He is the validator of Guinness' various records for eight-thousander summits. He knows everything there is to know about the topography of the 8000ers, and hardly anyone on Earth has seen more summit photos than him. As a result, he can usually tell at a glance whether or not a picture was taken on a particular peak. One of those who might have seen more summit photos than Jurgalski is Rodolphe Popier, contributor to 8000ers.com, who knows the morphology and rock formations of the various summit regions better than anybody in the world. He is also an analyst for the Himalayan Database.

More than ten years ago, initiated by a questionable summit on Annapurna, Jurgalski started to check many more summit proofs. With the help of some international experts, he started to dig deeper into the analysis. The research eventually took ten years and he had a hard time figuring out how to handle the results. They showed that most of the climbers on the list of 14x8000 had not all been at the highest point of all mountains, or could not/would not confirm it. In some cases, we are talking about climbs from 30-40 years ago, before the GPS era. The differences are typically not large between the points reached and the summit, ranging from 30-40 metres to about 190 metres in distance, and up to 45 metres in altitude. Jurgalski does not assume the differences were intentional, as climbers may have thought they were at the highest point, or had zero visibility, or, after climbing a brutally difficult new route, turned back 60 metres from the summit before an impending storm. What does sixty metres matter, you might think. And that is the epicentre of the whole controversy.

Sensing the historical weight of his findings, Jurgalski first put the issue up for social debate, for the community to define tolerance zones, i.e. to 'accept' all previous climbs up to a certain point, still sufficiently close to the summit. He did not want to rewrite climbing history (nor does he want to do so today). However, there was little proactive proposal about tolerance zones, let alone a consensus.

After about a year and a half of waiting and stressful deliberation, Jurgalski decided to publish the results of his research, this time revealing the names of the climbers involved. And this has shaken the climbing world to its core.

Reinhold Messner was missing from the list of actual achievers, but only three of the 44 names were verifiably at the highest point of each peak at the time of the study's publication. This was interpreted by the majority as "Jurgalski's attempt to rewrite the history of mountaineering". The media has only put fuel to the fire. Although in fact, he did nothing more than publish a fact-based analysis in which he underlined that he did in no way want to question the merits of those climbers who might have made honest mistakes.

In the summaries of his detailed analyses he puts it this way:

“The partly sensational performances of Messner, Kukuczka, Loretan and other pioneers are not in question, they will remain the heroes of 8000ers climbing forever, but we all are human and we all are doing mistakes and should correct them, if we can or at least admit them.”

Jurgalski believes that "the summit is the summit". That is, the highest point of the mountain from which you can only go downwards. He is not the only one with this philosophy. Whether one has missed the highest point by accident or on purpose, by mistake, by poor visibility or by fatigue, for him the point is that one has not reached the highest point. He argued that even the founder of the Himalayan Database, the late Elizabeth Hawley, did not recognise a climb where the climber turned back 30 metres in distance before the summit of Mount Everest. There are many examples where the climber went back up a mountain, because, after reporting to Miss Hawley, she said 'fine, fine, but you didn't summit'. The best known example is the American Ed Viesturs, who was “sent back” to Sishapangma by Miss Hawley after he had climbed the Central Peak, and not the main summit. Miss Hawley told him that he could only qualify for the 14x8,000 series if he climbed the main summit. The distance is 300 metres, the difference in altitude is 19. Viesturs went back and climbed the main summit of the mountain.

Some of the climbers involved are no longer alive. Others are too old to have a chance to “correct”, and some consider the case pathetic and are furious about the "centimetrism". The latter, including Messner, don’t care about such details. As Messner is quoted in a New York Times article:

“If they say maybe on Annapurna I got five metres below the summit, somewhere on this long ridge, I feel totally OK. I will not even defend myself. If somebody would come and say, this is all bulls**t what you did? Think what you want.”

But Jurgalski is the first one to acknowledge the legacy of Messner:

“No BS at all, with so many great climbing achievements and significant expeditions he surely remains one of the best mountaineers ever, but as all humans can do, he obviously made a mistake. Yes, it was only 5 metres in altitude, but 65 metres in distance.”

However, Jurgalski also argues that if Miss Hawley did not approve the summit of an unknown climber who had turned back 30 metres in distance before the summit of Everest, why should Reinhold Messner be handled differently on another mountain? Because he is famous? Because he has otherwise laid down an inimitable legacy in climbing the world's highest peaks? Where is the consistency here?

When David Göttler and Hervé Barmasse blitzed up the southwest face of Shisha Pangma in 13 hours in alpine style, they turned back a few metres below and some distance away from the summit because of avalanche danger, so they didn’t summit. They were open about it. Does it lessen the merit of their climb? The answer is a clear no.

Jurgalski has come under very harsh attacks, especially by Messner in the German-speaking media. He has been labelled a “hair-splitter”. Many are attacking him because he himself hasn't climbed any 8000ers. Which is a nonsense, because on the one hand he has seen enough imagery to navigate 99% of current climbers blindly to any 8000er summit, on the other hand, interestingly enough, no one ever accused Elizabeth Hawley of never having climbed any mountain in her life, yet if she said your summit picture was not the summit, the climber didn't start to argue, but walked back and climbed it properly.

If you would like to know who has missed what and by how much, click on this link.

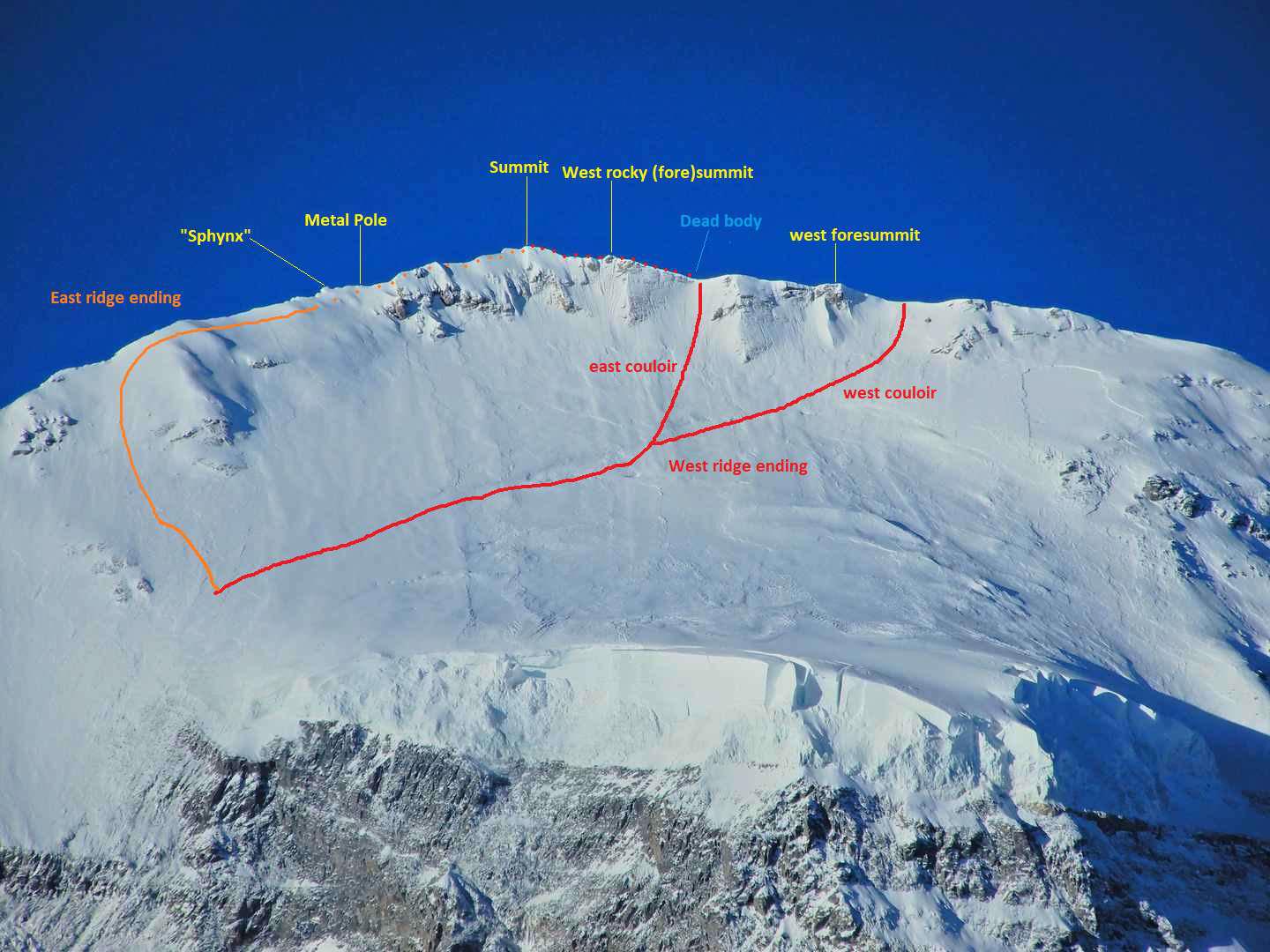

There are three 8000ers that do not reveal their summit easily. Among them, Annapurna (8091 metres) and Dhaulagiri (8167 metres) are problematic. Both of these mountains have long summit ridges with several high points, of which there is one highest point that is often called the true summit. These are not always easy to find, even in good weather, because of the similar-looking snow-ice corridors called couloirs, leading up to the summit ridge. You may come out on the wrong section, a few metres below the summit, and then, tired as a corpse, you have to try to reach the right point - provided you know which one it is. After an exhausting climb, it's easy to say "I climbed this, say what you will''. Totally reasonable. However, if you are after a record of some kind, it is your utmost responsibility to do everything you can to keep it clean. It's no coincidence that many climbers go back when they realise, even afterwards, that they have made a mistake. An excellent example is the case of the Italian Nives Meroi and her husband Romano Benet, who reached the so-called "Metal Pole'' on the summit ridge of Dhaulagiri, 140 metres in distance and 30 metres below the main summit, but it is not accepted as the highest point of the mountain, so they went back and climbed it properly. The same mountain resulted in Nirmal Purja losing his 6-month record (that he still claims) because he did not reach its main summit during 14 Peaks, only 2 years later.

The real troublemaker is the third peak, Manaslu, 8163 metres high in Nepal. It is often argued that the pointlessness of rewriting records is due to the lack of knowledge in the old days about which the highest point on the mountain was. If there is one mountain where this is most certainly not true, it is Manaslu. The first climbers were able to find the highest point of the mountain. In 1956, the Japanese Toshio Imanishi and Gyalzen Norbu Sherpa reached the main rocky peak of Manaslu. In 1974, the first female climbers of Manaslu, an all-female team, also reached the main summit, although one of their Sherpas thought of the foresummit that it was the summit. But the Japanese ladies insisted because they had seen the photos of the first climbers and knew what they were looking for. They too had "found" the main summit. Their full story can be read in the report they published in the Alpine Journal.

Sometime in the 2000s, it became fashionable to stop at the foresummit, or on some prominent point of the summit ridge. The nearest prominent point is 35-40 metres away and 8-12 metres below the main summit, and the last section is technically not easy to climb. The argument "what difference does 30 metres make" is certainly not valid here. It's whether you are able to climb the mountain or you are not. The Manaslu is advertised as an easy summit, an entry level 8000er, but it is those last thirty-five metres that are the mountain's venomous fang.

In the last decade, the reason why commercial expeditions have stopped earlier has simply been convenience. They'd anchor the ropes to a safe height, set up a selfie point with prayer flags, and head for home. Perhaps Australian climber, author and polar explorer Damien Gildea summed up the reasons best in this excellent essay:

"The researchers are also aware of the socio-economic reality that underpins modern Himalayan climbing, in that there is significant financial pressure on the Sherpas and other high- altitude guides and workers employed by so many aspirants to 8,000-metre peaks to have their clients feel they have been “successful.” Depending on the company and client, this may mean a summit bonus, which can encourage Sherpas to accept tops lower than the summit (especially if other groups are stopping there), or a bonus for simply getting their client over 8,000 metres, which may reduce motivation to continue to the highest point. With a slow, tired client in a line of similar climbers all close to the top of the mountain, and with their own safety also in mind, there is tremendous pressure on Sherpas to simply “call it good” short of the summit, and a grateful but inexperienced client may not know any better or simply not care."

For a decade, the problem was well known in the climbing community, but no one really wanted to address it. And because no one questioned its validity, it became the norm. Everybody knew that as soon as the problem got into the limelight, the achievements of all the previous climbers who only made it to some foresummit would have become questionable.

Then, in 2021, Jackson Groves took a drone shot of the summit climb that made the difference clear for even the absolute layman. While one team is taking “summit” selfies on the foresummit, in the background the other team is climbing to the main summit.

This was the breaking point. The pictures went around the world, and the topic made waves outside the community. Some commercial expedition agencies started to advertise their expeditions to the "True Summit" straightaway. There were huge slips in the interpretation. In many places, the phrase "the main summit of Manaslu has just been discovered" was used, which was obvious nonsense. Everybody knew it was there, it was just more convenient and safer for the agencies to stop at the end of the ridge. From there, however, there was no turning back. The only question was what to do with past climbers who hadn't been to the main summit. This would have been particularly painful for those having completed the Himalayan Crown series.

The Himalayan Database, in "consultation with commercial expedition organisers" (which is a bit strange from an independent organisation), took the diplomatic decision not to revise past climbs, but to accept only the main summit as a valid climb from the 2022 season:

"...the Himalayan Database has decided that from 2022 it will only credit the summit to those who reach the highest point shown in the drone picture taken by Jackson Groves. Those who reach the tops shown as Shelf 2, C2 and C3 in the picture will be credited with the foresummit. This change in summit accreditation is recommended and supported by foreign and Nepali operators who we have consulted in Kathmandu. As we cannot change history, we will make a note in the database that from 1956 - when the summit was first reached by Toshio Imanishi, Gyaltsen Norbu Sherpa - to 2021, we accepted the three points mentioned above as the summit due to a lack of in-depth knowledge."

The last sentence of the justification is not exactly true, as the problem was known to industry players long before, and Jurgalski's first analysis of the mountain had already been published in 2019. In any case, the Himalayan Database has stepped back and is willing to act only as a registrar, not as an arbitrator. Understandably, as the reactions to Jurgalski's later report show, too many interests would be harmed.

Many wondered what the point of all this was, the hairsplitting, the “questioning” of the achievements of the past. But those achievements have not changed. All that happened was that Jurgalski put into the public eye what really happened. He took nothing away from anyone, even if many still interpret it that way.

Without them there would be no way to find climbing records, and also the integrity of achievements would be questionable, as only the ethical standards of climbers would dictate what they claim. And there have been untrue claims even with the presence of the HDB and Jurgalski's 8000ers.com. The audience of 8000ers is already grossly diluted. The fight for sponsorship and fame and the pressure of social media, the urge for acceptance and recognition would be a huge temptation to overstate achievements. Without any sort of control climbing’s history and integrity would be in danger. We all should be thankful for those bookkeepers who do this job voluntarily for the service of the climbing community.

With the new information, the 14x8000 lists have been updated, opening the way for those who wanted to take the place of those on the records lists who had missed the highest point on even one of these summits. After all, they had not climbed those mountains "properly" and could therefore not be included in the statistical list. Suddenly, the "first woman on the 14 eight-thousanders", the first Hungarian on the "true summit" of Manaslu, and many similar national records, were once again up for grabs. And those who now have the financial means to achieve these goals can do so waaaay more easily than their predecessors, without any genuine climbing skills, and can gain media attention. And this brings us to the starting point of our article, how to go from fourth to first.

The first women to have come closest to climbing all 14 of the eight-thousanders were Basque Edurne Pasaban, Austrian Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner and Italian Nives Meroi. At the start of their careers, none of them set out to climb all fourteen. In an interview with Mozgasvilag, Pasaban revealed that she, for example, said six years after her first successful climb, her seventh 8000er, that she would aim for all 14.

By 2010, it turned out that all three of them had reached twelve of the fourteen peaks. The media started to pick up the story of who would be the first. They were trying to fend off the race, but Pasaban was clearly keen to be the first.

Then came the Korean Oh Eun-sun in the fast lane. Pasaban put it this way in an interview she gave us:

"It was quite a strange situation. We were three girls close to climbing all 8000ers: Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner, Nives Meroi and me. We were good friends: once one of us climbed a peak, once the other, so we progressed. Then in 2007 this Korean girl came along who had no Himalayan experience whatsoever. It was obvious when I first saw her on Shisha Pangma. She was already saying then that she wanted to climb all eight-thousander peaks. I said, go for it. But she was progressing very fast because she had a huge infrastructure behind her.

So as soon as she climbed one peak, she was taken by helicopter from one base camp to the other. By the time she arrived, a team of Sherpas had already fixed and tread the route for her up the mountain. This way, she could "collect" up to three 8000 metre peaks in a year. I never felt any competition from Gerlinde or Nives. I know how much effort it took for all three of us to get to the possibility of being the first. At different levels, though, as Gerlinde was much more technical, but I know how hard she had to work to save up the money for her expeditions. We had to give up a lot of things, such as a relationship or everyday life. And then when we finally get to the finish line, Gerlinde, Nives and I, along comes this Korean girl with all this money. Of course, our egos started to work. We worked hard to get there.”

To cut a long story short, Oh Eun-sun finished the series earlier than all three, but doubts were soon raised about her Kangchenjunga ascent. At the end of a long wrangle, the Korean lady admitted she was way short of the summit, so Pasaban took the record. Kaltenbrunner was the first to complete the series without supplemental oxygen, and Meroi was third, also without bottled oxygen.

After Jurgalski's report, however, it became clear that Meroi had not reached the main summit of Manaslu, while Pasaban and Kaltenbrunner had not reached the main summit of Dhaulagiri and Manaslu. This freed up the title of "first woman to climb all 14 8000er peaks", for which a new race soon emerged, this time by summit collectors with a full commercial expedition assistance. Norway's Kristin Harila, Britain's Adriana Brownlee (who meanwhile decided to take a break), Franco-Swiss Sophie Lavaud, Mexico's Viridiana Alvarez, Taiwan's Grace Tseng - who even claims records that none of her previous athletic performances can justify - , and China's Dong Hong Juan, who now holds the title. The latter was the first to finish the series, followed just a few weeks later by Harila, who completed the series in 1 year and 5 days, which is marketed as a “broken speed record”. It is a speed record but in a totally different category, not comparable to historical firsts, and surely nowhere near in mountaineering significance. The latest table can be found by clicking on this link.

Kristin Harila is a sympathetic Norwegian endurance athlete with no previous climbing background. (To avoid any misunderstanding, we mean technical knowledge and skills and independent climbing achievements under climbing background or climbing history.) She switched from cross-country skiing to trail running, then climbed Kilimanjaro in 2015. She added the entry-sixthousander Lobuche East, then the 7000er Putha Hiunchuli in 2019 and Aconcagua in 2020. Then she felt ready for Everest which she climbed being guided by three Sherpa guides, record Everest summiter Kami Rita Sherpa among them. She set a Guinness world record straightaway, climbing Everest and Lhotse within 11 hours and 59 minutes with oxygen. She then thought she would climb all 14 8000er peaks, seeing Nirmal Purja's (now proven false) six-month record. Because with the assistance available, and Purja's example, she clearly saw that it could be done. The biggest uncertainty in this project is whether the helicopter can fly, whether the client can stay healthy or whether the client will be given permission to enter or climb in Tibet.

Harila claims she is open about her style which is partly true. I agree, climbing claims should be honest. That is, and should have always been paramount. Unfortunately, that rule hasn't always been followed. But being honest doesn’t raise the level of an achievement, just like being honest about doping in sport doesn’t validate your success. Also, it doesn’t make achievements comparable. But when you are aiming for records, you ARE comparing your achievements to previous ones. If you break a record, the message is that you have been doing something better than your predecessors. And here is my point:

The problem is not the climbing style itself but how you want to market your achievement. Summit collectors are going for absolute records in mountaineering history, but they leave the most important factor out of the equation: assistance.

The climbers they compete with are all self reliant mountaineers who only dared to venture into the Himalayas after collecting decades of experience and knowledge, and then made ascents that have pushed the boundaries and became all time greats of the sport. Without guides and oxygen these new record seekers wouldn’t be in the position to even try serial climbing 8000ers in the first place. This is a huge difference. Surely Harila is an exceptional athlete but that is just the base to become a good climber.

Nirmal Purja broke a practically non-existent record because the time he “beat” (7 years 10 months and 6 days by Kim Chang-ho) was initially not aimed at being the fastest to climb all 14 and they did not use the same assistance. (Although we cannot overlook the fact that even Reinhold Messner sped up his climbs at the end of his series, switching to normal routes, to become the first to reach all 14 8000ers. But a speed record was not his focus, just to be the first.) During their careers, Messner and Jerzy Kukuczka were aiming for the hardest routes, many times solo or in winter, mostly on new routes, without oxygen and in alpine style. (Kukuczka only used oxygen once, when they made the first ascent of the South Pillar on Everest in 1980). They were not using oxygen because it is the lack of oxygen that makes 8000ers so special and hard. Since Messner and Habeler mountaineers know that it is possible to climb all of them without so that has become the elite sportive expectation. If Kukuczka or Messner wanted to do the 8000er series as fast as possible they might have done it within 2 years had they been willing to use oxygen and use the easiest routes. With today’s logistics, they all could do it in 3 months. It just never was their goal. Yet Nims talks about “shattering the previous record”.

The good side of Harila’s quest is that last year she already proved that it is not superhuman to climb all 14 within 6 months. This year she is close to finish it even in 3 months. It puts Nirmal Purja’s self-exaggerated and overclaimed achievement into perspective. A strong athlete with enough money and the right logistics can do it with a lot of oxygen, guiding manpower and helicopters. But let’s be honest: if you use oxygen, you are climbing 14 7000ers. Which is bloody hard, too, but again, the marketing campaign is about breaking absolute individual mountaineering records on 8000ers, and not about setting a new category of maximum assisted guided clients.

Of course everybody has the right to choose the style they want to climb in. Every style has its own right on the mountain. But if you really want to be honest then you should take every possibility to put your achievement into perspective in the media. None of these record seekers have ever mentioned that Kukuczka or the others were never going for a speed record, never needed a guide or oxygen, and opened routes that have never been repeated.

As a sort of defence of her style, Harila mentions that there is also a great difference among oxygen users in terms of how much oxygen they use or how many guides they need. Sure, good point. And there are those no-O climbers who outright lie about not using oxygen, and those who really don’t use it but have Sherpa support with a bottle on standby just in case, or using other people’s gear and food then saying they went light and fast, without assistance. The pressure of “sending”, of being exceptional, worthy of media attention, of getting sponsors creates these different categories where everybody can be the best and think that if they are honest and open, for them the category differences do not count any more. But they do. The problem is, these claimants will all be regarded on the same record lists by the general public, but it is only possible because the general public and the mainstream media does not understand the differences so anything could be sold if packed rightly.

Labelling her project “She moves mountains” while climbing guided by up to six male sherpas is outright disrespectful both to her guides and to climbing history. In fact, her Sherpa guides move the mountains for her. The controversy of changing her Sherpa team, or the alleged helicopter assistance to load gear and Sherpas to higher camps to prepare the route for her more quickly, do raise further questions about the standard of her project. Sometimes she acknowledges that it is a team effort but in fact she does not contribute to teamwork in any way, she is just making use of the work of the Sherpas. Yet it is her name that makes the headlines, as if it was only her outstanding capabilities to achieve this record. There are many outstanding endurance athletes out there who could do this with the same assistance..

Of course, there were already differences in climbing style between Pasaban, Kaltenbrunner and Meroi, but all three are common in that they can also stand their ground as individual climbers. Pasaban climbed in the traditional expedition style, not with a mountain guide but with the help of experienced companions and high-altitude porters. She used supplemental oxygen only on one peak, Everest. Nives Meroi and Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner climbed all 14 summits without supplemental oxygen. Meroi and Kaltenbrunner have climbed without the help of high-altitude porters, but Meroi stuck to normal routes, mostly using ropes fixed by other expeditions, while Kaltenbrunner often climbed in alpine style and on much more difficult routes than the normal routes. Climbing the northwest ridge of K2, or traversing Shisha Pangma from the South to the normal route would be a remarkable feat even for a male climber.

When asked about the importance of being first, Kaltenbrunner replied:

"If records were the only thing that mattered to me, I would have taken the easiest route everywhere. For me, being first is of no value."

The only thing missing for Meroi after the revision is the Manaslu main summit. While still active, she could go back, but the crowds make her reluctant. Instead, she and her husband (who has been her partner on all the climbs) teamed up with Slovakian Peter Hámor and Slovenian Bojan Jan and successfully climbed the so far unclimbed west face of Kabru, 7394m high next to Kangchenjunga. This gives you an idea of what she considers to be the more challenging climb.

And this brings us to the main point of this article.

The real problem isn't the “centimetrism” as some call it, or the business opportunity to set new records because of mistakes that were discovered decades after. The problem is that most people wrongly associate the 8000ers series with climbing value and climbing performance. It is as if the 8000ers were the measure of the climber. But the value of a climber is not determined by how many of the highest points of the eight-thousanders he has reached, or whether he has climbed Everest, but solely by how he got up to any mountain.

Reinhold Messner is the world's most famous mountaineer, and the first thing that is typically highlighted about him is that he was the first to climb all 14 peaks above 8,000 metres. This effectively cemented the fact that the climber of all 14 8,000 metre peaks is an extraordinary mountaineer. But in Messner's unprecedented career, 14x8,000 metres is only a statistical curiosity, it is not what makes him one of the greatest alpinists who ever lived. He was already considered one of the world's best climbers before he set foot in the Himalayas. It's the 'how' of his performances on the 8000ers that makes him one of the greatest.

Messner was constantly pushing the limits of what was possible. Not in the way the over-self-marketed Nirmal Purja pushes the limits of mere logistical possibilities, but the limits of physical and mental capabilities and climbing technical prowess. In his climbing projects, not infrequently even survival was not guaranteed. Willing to take the greatest risks for his vision, almost all his ventures were literally explorations, with many unknowns and countless first ascents. The first crossing of Nanga Parbat, where his brother died on the way down, and he himself barely survived. The first ascent of Mount Everest without bottled oxygen with Peter Habeler. The first solo ascent of Mount Everest without the use of supplemental oxygen, with no one else on the mountain. First solo of Nanga Parbat. The first alpine-style traverse of Gasherbrum I - Gasherbrum II with Hans Kammerlander, which fundamentally changed the style of climbing on the eight-thousanders. North face of the Kangchenjunga. Any of these climbs have more climbing value than collecting all 14 8000ers with a mountain guide. He may have been 65 metres away from the summit of Annapurna but that doesn’t change anything in his legacy or mountaineering value. It does change whether he can claim to have climbed all 14 though. But the point is, it doesn’t matter.

Already in the golden era, it wasn’t the "how many", but the "how" that gave the value of the climbing achievement. By today, the sporting value of collecting 8000ers has been completely devalued because of the guided record seekers.

The purely numerical approach of climbing 8000ers was at first equivalent to the climbing value, since until the second half of the 1980s only the best climbers attempted these peaks, often on new and difficult routes, sometimes in alpine style or even solo, then in winter. However, with the emergence of commercial expeditions, i.e. guided extreme high-mountain tourism, the statistical achievement has clearly separated from the climbing value. Nowadays, almost anyone can climb a series of 8,000m peaks if they have the financial means, above-average physical fitness and enough free time. You don't need to be an independent climber in the classic sense. The current female serial climbers will never even come close to the great female climbing figures such as Allison Hargreaves, Wanda Rutkiewicz, Lynn Hill, Catherine Destivelle or Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner. Just as the lifetime achievements of Messner, Kukuczka, Wielicki, Stremfelj, Bonington, Urubko or other climbers of their calibre are not affected in the slightest way by the modern era of guided peakbaggers like Shehroze Kashif.

The same applies to the Seven Summits or the Explorer's Grand Slam series. If you ski the last degree (111 km) to the North and South Pole in a guided group, it is nowhere near the feat of skiing the full distance of almost a thousand kilometers unsupported and without guides. Not to speak about the meaning of the world "exploration". What do you explore on a route already walked by hundreds or even thousands of people, except for your own limits?

The word 8000er has a mythical aura around it, mainly because of the many casualties and heroic stories of the past. It only gets in the news because people still think climbing 8000ers requires the same commitment and climbing craft as 40 years ago. But it is only true if you forego oxygen and Sherpa assistance.

We know commerce has never been about quality. In times when Eddie Bauer fires their climbing ambassadors to make room for influencers to reach a broader market we should not have high expectations about which direction the industry is heading.

Unfortunately even specialised media are obsessed with 8000er successes and most do not shed light on the style difference and how these summits were archived. They give too much limelight to many climbers who are nowhere near the capabilities of their predecessors whose records they “break”. And those who try to stick to original values, climbing without oxygen and support, have a hard time to make people understand the difference.

The Czech alpinist, 2-time Piolet d'Or winner Marek Holecek summed this up perfectly in a social media post:

"I do not think that the wider climbing community or the public is changing. The 14×8,000’ers as performed by Nirmal Purja, or the Nepali winter ascent of K2, still attracts the media like a magnet. And it is the media who form the views of most readers. To illustrate: In February 2022, National Geographic magazine published an article on the winter ascent of K2 under the headline ‘A Climb for History'. Also, the major documentary Beyond Possible is running on Netflix, where Nirmal presents his ascents. According to the great interest, the media and the public obviously do not care where these stories stand in the real history of climbing, whether they respect the code and correspond to development. In my view, big words, but empty content."

It is questionable whether specialist media should even cover guided 8000er climbers, just like we don't report about guided Mont Blanc climbs. Easy-to-use PR statements lure publications to get clicks without too much effort put into it. But if the economic pressure of the clicks still lingers, at least cover these climbs with the exact and right context and explain what a "record" really means and how it was achieved. When people like Grace Tseng make headlines in international climbing media, it is embarrassing to mountaineering.

There surely are many compelling, inspirational and touching storylines behind guided climbers. It’s a fantastic thing that many people can achieve their dreams with the help of guiding assistance and they surely can inspire other people to step out of their comfort zone. But those who need a guide to climb a mountain should in no way claim any absolute mountaineering record.