- Futás

- Hegymászás

- Kerékpár

- Túra

- Sí

Since appearing on the scene, Ms Tseng has made headlines with different climbing records, which seem to be her main motive to set foot on a mountain. She openly set out to be the youngest to climb all 14 8000ers, for which quest she now has serious competition, with other such 'climbers' entering the race. But she claims to be the first female to summit Kangchenjunga in autumn, the youngest female to summit Annapurna without supplemental oxygen, the first Taiwanese to climb K2, the youngest female to climb K2 without oxygen, the youngest female to climb the five highest mountains on Earth, the list goes on. She claims to have climbed 12 of the 14 8000ers, starting with Manaslu’s foresummit in September 2019. Her ridiculously filtered summit photos raised many eyebrows, but together with her summit videos all seem to be legit. For the first blick. But, if you look a little closer, some details catch your attention.

However, nobody really doubted her achievements outside of Taiwan until she announced something too big. A 13-hour speed record on 8163 meter Manaslu in October 2022, without oxygen, with the same time as the male fastest known time set by the ski mountaineering champion and one of the strongest alpinists of his generation, the Italian Francois Cazzanelli. Nobody in the climbing community believed it. Now it was time to look a little closer.

Along with a few foreign journalists we started a parallel investigation. I have asked her a myriad of questions, first publicly, then privately. I was trying to figure out the conditions of the climb, answers to the contradictions of the circumstances, and most importantly, her athletic capacity. She answered many questions, but avoided giving any specific data on her training or endurance capacity, giving only general answers. She could not even tell her VO2 max – she did not seem to even know what that is. She insisted that her previous four 8000ers in Pakistan (which she claims to have climbed without supplemental oxygen) climbed in July had given her so good acclimatization that it enabled her to climb that fast. But 274 meters/hour climbing rate without oxygen at almost 8000 meters from a non-athlete with no endurance past is an incredible number, especially considering that in the previous hours of her climb the climbing rate already fell way below 200 meters/hour. Many people questioned the originality of her provided evidence, her summit photos and videos, and even her GPS track. Since they were the last team on the mountain, there are no witnesses, except for her three Sherpa guides who were hired and paid by her. They even signed a statement to back up her claim of having climbed without oxygen and in 13 hours from base camp to summit. On her part, she considers the case closed, having provided evidence, and threatens to sue anyone who publicly questions the originality of these proofs and hurt her reputation.

But that analysis should be the topic of another article.

While the investigation about Manaslu is still ongoing to find out how she did it, my attention turned to her previous 8000er claims, and I started with the autumn climb of 8586 meter Kangchenjunga. While recently talking to my good friend Kris Annapurna, who is a great chronicler of alpinism and avid follower of 8000er seasons, we found out that she had been also investigating Kangchenjunga. We have shared our personal observations with each other, and we have reached the same conclusion that we describe below, which confirms the doubts we had about this ascent.

In October 2021 Grace Tseng announced that she and her four Sherpa guides have summited 8586 meter Kangchenjunga, using supplemental oxygen. No female climber has ever scaled the mountain in autumn, and no other person has succeeded in the autumn season for 17 years. That is a bold feat on a very difficult mountain.

What caught our attention was that none of their summit photos or videos showed a broad panorama from the summit, even though the weather was excellent. If there is a summit which offers spectacular views, it is Kangchenjunga. From the summit of Kangchenjunga you’ve got one of the most stunning 360-degree panoramas. If you scroll through other Kangchenjunga summit photos and videos from the past, made in good weather conditions, they all show you breathtaking views. There are even some climbers who write the names of the visible peaks for the audience. How could Ms Tseng miss this opportunity?

I asked her to provide GPS tracks to all her previous 8000er climbs, which she denied, saying it contained her private information, so it wasn’t convenient for her to disclose them. So we had to rely on the photo and video material, and their own description in various social media posts.

With their summit photos at an unrecognizable place, and Ms Tseng’s later posted summit video not showing the usual Kangchenjunga vistas, we tried to get answers to our suspicion.

In autumn 2021, a total of two different teams were at Kangchenjunga, both aiming for the normal route (southwest face), but not operating on the mountain at the same time.

On September 8, 2021, a team of 8 climbers, led by the Ecuadorian Esteban “Topo” Mena, arrived at base camp. The party included Carla Perez, client Jan William Werner, and five Sherpas: Dorje Sonam Sherpa, Mingma Tshering Sherpa, Palden Namgye Sherpa, Pasang Sona Sherpa, and Pemba Gelje Sherpa. On this date and until their expedition lasted, this group was alone on the mountain. They did not summit, and the highest point they reached was at 7,430 m (their Camp 4), on September 18, 2021.

According to the Himalayan Database, Topo's group reported that the conditions on the mountain were difficult. It was too warm during the day and even during the night. Avalanche risk was moderate. It snowed a few times, during the time they were there. The snow never consolidated properly as the temperature was too warm. They used supplemental oxygen from 7,000 m to 7,430 m. They fixed ropes all the way from Base Camp (5,200 m) to Camp 4. They left the fixed ropes on the mountain for the Nepali Nima Gyalzen from Dolma Outdoor Expeditions, and Grace Tseng, his client, from Taiwan, who came in after, according to their report. When they cleared Camp 3 after the expedition, there was a big avalanche between Camp 3 and Camp 4. Due to a serious family matter involving Werner, he had to return home immediately, so Topo Mena's group ended the expedition. Mena's group left Base Camp on October 11, 2021.

Under the 'leadership' of Grace Tseng, the group arrived at Kangchenjunga Base Camp on October 8, 2021. Earlier, they summited Dhaulagiri I, with a brief stop in a nearby town, from where they took a helicopter to reach Kangchenjunga Base Camp, when Topo's group was already packing up their base camp to leave the mountain.

Ms Tseng's group consisted of:

Grace Tseng as 'leader', Nima Gyalzen Sherpa and Dakipa Sherpa from Dolma Outdoor Expedition (agency), and two other Sherpas, Gelje Sherpa (who is now a guide in Seven Summit Treks, and was previously guide in Elite Exped), and Pasang Rinzee Sherpa.

According to The Himalayan Database report, on October 15, 2021, Nima Gyalzen and Pasang Rinzee fixed the rope to 8,000 m. Gelje himself published on that day, that he had been fixing rope up to 8,050 m on October 15, near the couloirs. The Sherpas returned to Camp 4 (at 7,500 m) at about 3.30 PM, on October 15, 2021. Then they had a short rest, and at 5.45 pm PM on the same day, October 15, the team, together with Grace Tseng, started their summit push. Nima Gyalzen and Gelje went ahead to fix the route to the 'summit'. They claim to have reached the summit at 1 PM, on October 16, 2021. All team members used supplemental oxygen, according to them, from Camp 4 to summit and back to Camp 4. As Pasang Rinzee recounts on his Instagram, the descent from the (supposed) top took them more than 7 hours to reach Camp 4.

Pasang Rinzee Sherpa subsequently shared several videos on his Instagram, as well as photos of the ascent. According to his account, and as we can also see in the report they sent to The Himalayan Database, their summit push from Camp 4 to the (supposed) summit lasted 19 hours and 15 minutes, which is a lot. Properly, Grace Tseng also shared videos and photos soon after on her social networks, in one of them she commented: "seeking the summit". But had they really found it?

The average duration of the Kangchenjunga summit push from Camp 4 (depending on terrain and weather) is approximately 10 to 14 hours. This means that 19 hours with three people already possibly exhausted from the previous day (fixers up to 8,050 m) and probably due to insufficient oxygen bottles, could have made it unfeasible to continue progressing towards the summit. When Mingma G and his team were trying to summit Kangchenjunga on a recent expedition, they had to turn around on their first summit push from 8,400 m, because it was too late to continue towards the summit.

Kangchenjunga is a mountain whose final section is extremely exhausting. Several climbers have already told it during the climbing history of this mountain, that the higher you climb, the more difficult it is, and the last section of rock climbing is more demanding, where the ropes often break.

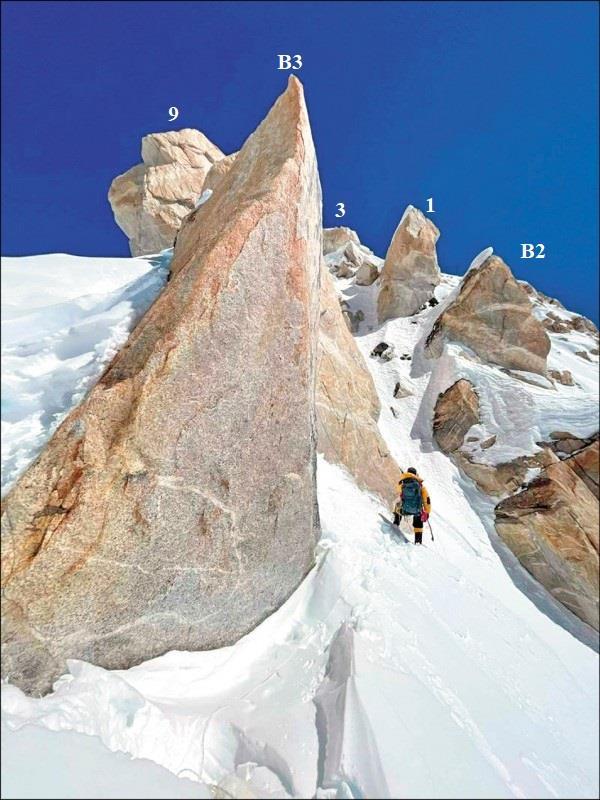

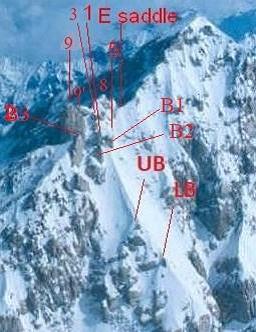

As their videos posted on social media, the team apparently deviated to the left of the normal route above camp 4, and they were climbing towards a huge, diamond-shaped boulder, a clearly visible feature even from afar, on the left side of the couloir. This area is called the Pinnacles. By now they already came off of the normal route. In a video posted by Pasang Rinzee you can see a very slow moving Tseng who needs help to advance, and looks visibly very tired.

To reach the summit from here would have taken hours. They would have needed to get down to the saddle before the summit then join the normal route and the long traverse to go around the summit pyramid. Being on the summit push for 19 hours, with oxygen running out, having missed the route, and also late in the day, with a difficult descent ahead, this would have been way too risky.

The summit portraits and the video of the quartet standing on a snow ridge, presumably purposely filmed from a below angle, are useless to prove they were on the summit.

However, there is one video and one photo that helps to orientate the group’s position. The summit video of Ms Tseng, which contains a selfie, then shows a very narrow angled panorama gives us the necessary hint, with recognizable features and mountains in the background. In this video she takes out the Taiwanese flag, behind her is one of the Sherpas walking up to a higher point, supposedly their summit, but it is not the summit of Kangchenjunga.

While the selfie mode always shows the reversed angle (like a mirror), we need to horizontally reverse the photo to get the original view and direction. This is the reversed angle with the real view, with Yalung Kang in the background. Sherpa walking up to a place that is not the summit:

If you look carefully, in the reflection of her sunglasses, you can see a snow bump that looks very much like the one they are standing in front of on their solo summit portraits:

Her panorama photo looking south that she posted on Facebook clearly shows a view that is not possible to see from the summit. That lower part of the South Ridge (centre of picture) is not visible from the summit:

This is what you should see looking south if you stand on the summit of Kangchenjunga (Screenshots from ):

Looking downwards from just below the summit, the view is like this (Screenshot from this video)

I tried to get a confirmation from Ms Tseng whether her photos and videos were all made at the same place, just looking in different directions, but she did not answer. Afterwards I was blocked from her public Facebook page.

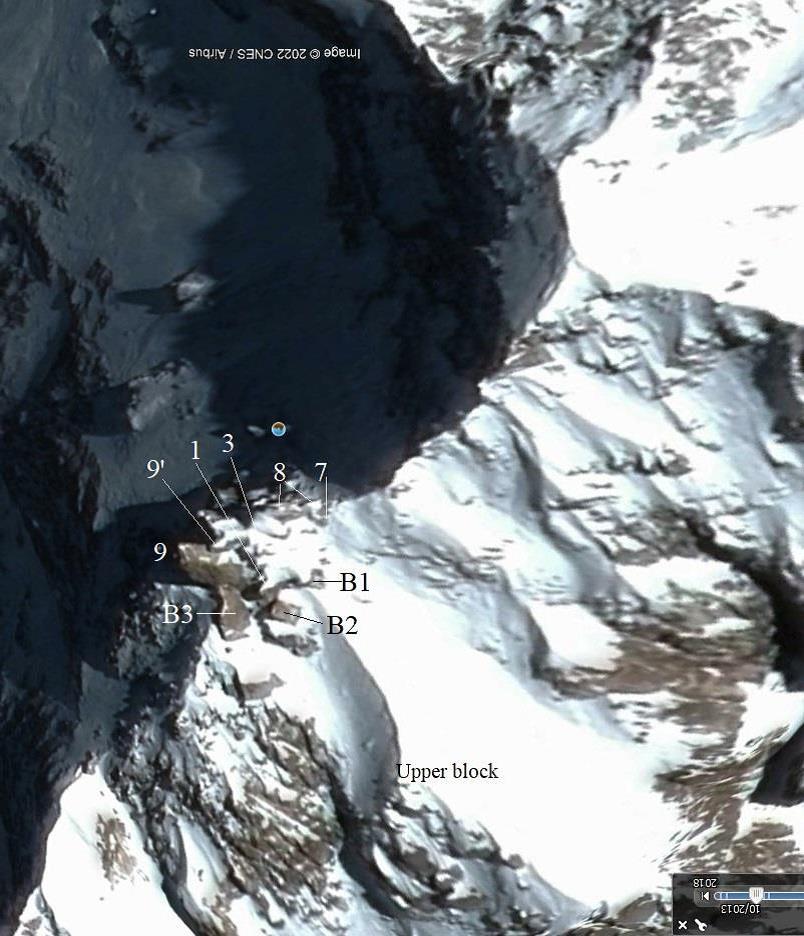

Comparing the provided photo and video evidence with other climbers' summit photos and videos, Grace Tseng and her team did not reach the main summit of Kangchenjunga on October 16 2021. They took their summit photos and videos west from the summit, above the Pinnacles area, at an approximate height of 8480 meters. In perfect weather conditions it is unimaginable that they would not have shot a panorama that shows the northern and eastern view from the mountain. This is what they would see from the summit to the North and East:

Short answer: Somewhere there, see yellow dot (screenshot ):

That huge, diamond-shaped boulder is visible in their videos. Rodolphe Popier, analyst for 8000ers.com, made these graphics, to better understand the position of the Pinnacles area, and its distance from the summit. Take the diamond-shaped boulder (Nr. 9) for reference:

After many hours that we have dedicated to this study, both me, and Kris Annapurna on her part, in a long conversation we realized that we had the same observations. Before publishing our conclusion, I shared our doubts with my good friend, the renowned chronist Eberhard Jurgalski from 8000ers.com who informed us that they had already been working parallel on the Kangchenjunga case, even for a longer period than us.

They confirmed our findings. A few days later they completed their detailed research report, which has already been shared with The Himalayan Database to revoke the Kangchenjunga summit claim of Grace Tseng and the four Sherpas. The report will be published on 8000ers.com soon, and we will update this article with a link to it as soon as it comes out. Ms Tseng's other 8000er claims will also be investigated.

Since the accompanying Sherpas also reached records with their Kangchenjunga claim, those will also be revised.

Mozgásvilág is Hungary’s premier online outdoor magazine. Our primary aim is to inspire people through great stories. However, all of those great stories must be true. We cannot keep our eyes closed when we clearly see which means mountaineering records are re-written with. We don’t intend to harm anybody’s reputation but are keen to speak out for fairness and climbing’s integrity.

Once reserved to the very top of elite mountaineers, high altitude climbing has become a playground of almost anybody with an above-average fitness level, using the commercial expeditions' full service package. Exactly because of this available commercial expedition assistance, today’s 8000ers summits are way overrated. Yet these guided 'climbers' compete for the same accolades, they get on the same lists as real mountaineers. A real mountaineer doesn’t need a guide.

Being a non-regulated sport, high altitude climbing is a goldmine for fame- and record seekers who simply exploit the sport to sell paid-for achievements to the general public who cannot differentiate. 'Record' and 'first' are the most important words to get sponsors. Although there are no rules, there are ethics within the climbing community. Being honest has always been the paramount rule, but of course it has happened many times in the past that claims turned out to be false.

There are several great climbers who have achieved many great feats in the world of 8000ers, sometimes paying with their own life for their visionary dreams. Those climbers deserve to be challenged by real mountaineers and honest achievements.

In today’s social media machinery it is ever harder to judge the credibility of these types of claims. It is our responsibility whether we want to keep these ethics. The work of institutions like 8000ers.com and The Himalayan Database have never been so important than now. The bad news is that besides Ms Tseng’s false Kangchenjunga summit claim there are several other suspicious climbers' announcements. This case is only the tip of the iceberg.

Ms Tseng is already preparing for a speed record on Everest next spring.

Hereby I would like to thank Kris Annapurna for the great cooperation. Without her contribution this article could not have been written. I am also grateful for the friendship of Eberhard Jurgalski and his painstaking efforts to keep climbing records' integrity.

You can comment on this article here.